Long Lost Article on Creede Rep from Nov ’68 KU Newspaper

A Dream Realized. The Living Theatre Comes to Creede

Originally published in the Nov. 1968 volume of the University Review, University of Kansas

A community without a theatre is like a community without a church. A theatre, like the church, must speak to the spiritual urges of the community it serves. The function of a theatre in contemporary society is to fill a vast emptiness left by the mechanically reproduced banalities of television (the term “vacuum tube” is equally appropriate, really) – a vacuum, indeed, that was foreshadowed by William Shakespeare when he wrote: “What light through yonder window breaks? It speaks, and yet says nothing.” The inescapable fact about the live theatre is that it utilizes LIVE actors. That is a tautology but it’s worth thinking about: the realization, the identification, the recognition by the members of an audience that there, before their eyes, is a fellow human being recreating for them still another human being–his thoughts, his actions, his character, can be the most profoundly moving artistic experience in all their memories. Yet, the theatre in America today still remains largely centralized. Live theatre is unavailable to most communities, largely due to their own indifference or casual preference for “Brand X” to be found at the easy turn of a dial. Happily, there are exceptions.

The silver mining town of Creede, Colorado, (pop. 450) could hardly be considered at first view to be a likely prospect for a repertory theatre functioning without subsidy three months out of the year. By way of comparison, the Lyric Opera of Kansas City, (pop. 1,000,000+) operates a four week season of full repertory with seventy percent of its budget subsidized. That is, thirty percent of its budget is received from the box-office. The town of Creede, lying high in the Rockies at the headwaters of the Rio Grande is seventy miles from any city of consequence (Alamosa, pop 10,000), fifty miles from a doctor, and thirty miles from just plain anything. Visitors are amazed that they have to drive THROUGH either Wagon Wheel Gap or Slum Gullion Pass to get to Creede. The town was founded in 1892 as a silver mining camp and in the tradition of the Big Rush grew from nothing to a teeming tenet city of ten thousand miners, forty-five saloons, forty hotels and ten brothels (no churches or theatres) inside of a year. In its short but colorful career as a boom town Creede hosted such notables as Bat Masterson and Bob Ford (the man who shot Jesse James and who himself was killed in a bar-room fight in Creede.)

Eventually, the claims failed one by one as the lust for quick wealth drew the silver out of the surrounding mountains. In ever increasing circles the giant mining operations: Anaconda, Commodore, Lost Inca, Equity, Kentucky Belle, stripped the mountains of their trees and plunged deep tunnels–some stretching for many miles under the solid earth. With the inevitable diminishing returns of mining and the falling price of silver, Creede ceased to prosper and by about 1912 the population had dwindled to its present level. Creede is listed in the 1967 AAA “Travel Guide to the Western States” as a ghost town–much to the amusement of its 450 hardy citizens and to twenty-six young performing artists from the University of Kansas who for three summers have run a perfectly successful repertory theatre in a town that supposedly couldn’t support a movie house.

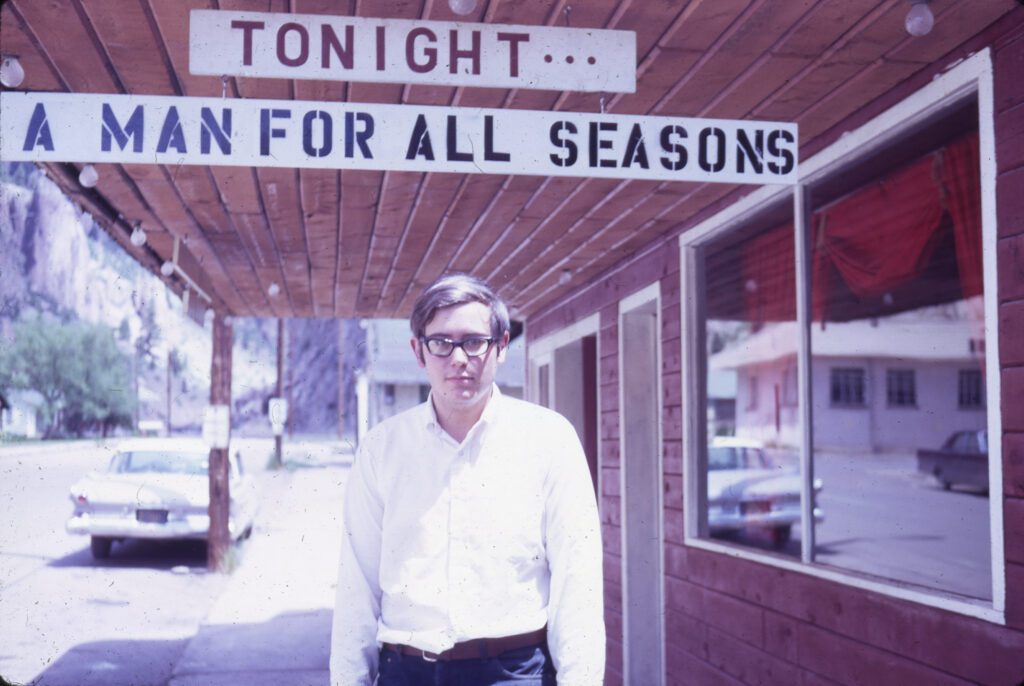

It is next to impossible to consider all the elements that went into the chemistry which made the venture a success, but three outstanding features demand attention: 1) the desire on the part of the community at large spearheaded by the town Jaycees (Junior Chamber of Commerce) to create and sustain a living theatre; 2) the drive and brilliance of the theatre’s first director, Steve Grossman; and 3) the devotion to their art and unswerving determination in the face of unbelievable adversity of twenty-six young actors and actresses.

The Creede Jaycees, who boast a membership of all the men in town between the ages of 21 and 35, as a community service organization were faced with a community problem: the town enjoys a large tourist influx during the day when the picturesque buildings, survivors of the boom days, can be seen and photographed. The night life in Creede, however, is such that a dog can sleep on the main street with impunity from about seven o’clock in the evening onwards. There are of course three bars: “The Golden Nugget,” “The Silver Dollar,” and the “Hotel Bar.” The bars, however, can only offer so much entertainment and solace to the people in Creede, and, more practically speaking, only draw so many people in from the surrounding guest ranches during the evening. Initially, the fact that Creede was in the center of a developing tourist area and that Creede could take measures to exploit that fact beyond the resources of the three bars, motivated the Jaycees to explore the possibilities of a summer theatre for the town. They wrote a letter to the theatre departments of various universities in the region, asking if any of them would be interested in organizing a summer “Mellerdramer” in Creede. Several schools officially responded including Denver University and the University of Colorado. All the interested parties, however, withdrew their interest when they learned more details about the town–its population, available facilities, etc. The Jaycees letter was posted on the Murphy Hall bulletin board and drew the attention of Steve Grossman, a junior theatre major and aspiring director. Steve phoned Jim Livingston, the acting president of the Jaycees and agreed to drive out to Creede the following weekend and survey the town.

Steve Grossman made the trip in the Spring of 1966, saw the ramshackle “Opera House” which had stood abandoned for several decades, saw the people of the town whose life was built around what was left of the mining industry and concluded through a combination of insanity and courage that the operation was, in fact, possible. Thus, “Operation Summer Theatre” was born. For the next two months the project was divided between Lawrence, Kansas and Creede, Colorado. In Creede the Jaycees set to work rebuilding the inside of the Opera House and making livable an old “boarding house” (actually the largest and most successful bordello in more prosperous times) into living quarters for the acting troupe. The Jaycees would get off work at the mines about four in the afternoon and work far into the night: the stage had to be completely rebuilt, the walls of the auditorium shored up, a hotel oven weighing several tons to be carried by hand up a winding staircase to the “Silver Palace” as the dormitory is now called. The list of accomplishments goes on and on. Advertisement had to be secured, lighting equipment such as dimmers had to be begged, borrowed or stolen, and arrangements with the owners of the building had to be carried out. Meanwhile, back in Lawrence, Steve Grossman went to work selecting the company members and the plays for the first season. Neither process was easy but both had to be quickly accomplished. Many of the more seasoned actors in the theatre department were interested at first but had second thoughts when they realized the “impossibility” of the undertaking. It is a decision which many of them have regretted ever since. The actors who did choose to go were predominantly young but their talent was soon to be proven beyond doubt. After many all night sessions Steve chose a season based on two often conflicting sets of criteria. First, the question was asked: which play would have the most commercial appeal to the townspeople and the summer tourists? Second, which plays could provide the most successful artistic experiences? Compromises were made. Shakespeare, Pirandello and Ibsen had to be set aside at least for the first season. The final selection was: “Mister Roberts,” “The Bat,” “Our Town,” “The Rainmaker,” and “Born Yesterday.” With no assurance but hope thirteen actors set out to live and work in a town which only two of them had ever seen.

The first week was a nightmare. “Mister Roberts” was to open ten days after the company arrived. Finishing touches had to be made on the theatre, a whole rewiring job done for the lighting system, scenery (starting from scratch) had to be built and a show rehearsed–all in ten days time. Looking forward with increasing desperation to the opening on Sunday every member of the company worked night and day (sleeping in two-hour shifts) from Wednesday until curtain time on Sunday evening. Rehearsals began at nine in the morning and ended at five. Scenery construction began after dinner and continued until breakfast. The expenses mounted and some of the Jayees began to panic. Some wanted to send the company home and forget the operation but others kept the faith. By Sunday evening the company was six-thousand dollars in debt and at the point of mental and physical collapse. No one could predict how the show would be received since the only live theatre many of the first night audience had experienced was the local, amateur Mellerdramer which is a summer institution in many parts of Colorado. In the makeup room below the stage (actually a converted coal bin) there was much talk of going home the next day when the theatre closed. As the audience filled the one hundred and forty-four seat capacity of the Opera House there was a sense of great fear more intense that the usual “butterflies” which accompany a performance, but there was also, despite the great fatigue, a sweeping sense of elation and pride among the company that they had come even this far. They were going to open a show that night so they still had their dream.

What was that dream? Steve Grossman was the one who could articulate it best when he echoed the words of a sculptor friend of his back at K.U. who used to say when he had gotten his equipment ready to start on a new project: “I got my handy-dandy tool kit and I’m gonna make art.” Steve knew, and the company eventually realized, that the belief in what you were doing was the indispensable ingredient of success. As a genuine performance in the theatre is impossible without deep sincerity on the part of the actor, so accomplishment in a broader effort is impossible without the will to believe. That kind of confidence in the face of the odds that were present in the first, second and even third summer in Creede requires a special kind of insanity possessed by few individuals. Steve had it and it was catching. It finds parallel in the neurotic-creative compulsions of a Dostoevsky or a Beethoven. Steve was a director who tore into the project of staging a play like a tornado of creative belligerence and he offended many people who didn’t share or understand that capacity. Ultimately, however, it was not only successful but a necessary ingredient for success.

As word is necessary about the people of the town. The educational level in Creede is not exceptionally high. The average male goes to work in the mines after high school, and if he survives to the age of thirty or thirty-five, he will retire from underground work and take a job in some related but less demanding field such as driving the ore-trucks down from the upper mines or working in the main office in town. The average girl marries a local boy after high school and sets about raising one of the unusually large families which typify the town. Almost everyone in town is related to everyone else. Thus, the town is dominated by a kind of hierarchy of old families with close interconnections. The Birdseys, the Leggits, the Turnipseeds and the Husselkusses are families that are proud to trace their lineage back to the boom of 1892. The people of the town have an attitude towards life which is shaped by the constant factor of sudden death or serious injury. Rarely does a year go by without at least one death in the mines. No one in town has escaped losing at least one close relative, father or spouse in a mine accident and this factor has given to the people a sensitivity to tragedy that most theatres cannot count on in their audiences. Thus, Mrister Robert’s death took on a special significance, and thus, the simple explorations of every day life and death in Grovers Corners of Thorton Wilder’s “Our Town” won the hearts of many of those good people who saw in it a personal relevance more intense than that of a more “sophisticated” audience. One tough, burly former miner, now the town’s deputy marshall, came to every performance of “Our Town” and wept openly. The company later learned that his first wife had died in childbirth and that he found in the theatre a reflection, perhaps even an articulation, of his most profound attitudes toward the inevitable process of birth, childhood, growing up, death and eternity. In this quiet town, with death as an omnipresent reality, there is a great enjoyment of life. Therefore, Emily’s lament in Act Three of “Our Town” took on a special meaning: “Oh, Earth–you are too wonderful for anyone to realize you.”

The majority of Creede audiences, however, come from the tourist population. For the most part it must be admitted they prefer (as some of the townspeople prefer) the light, non-philosophic comedies, so accurately labeled as “Broadway Fluff.” Since the theatre relies on success at the box office for its continued existence, plays in the genre of “Barefoot in the Park” are inevitable fixtures in the repertoire. Those dedicated to the overthrow of the “tired businessman’s” theatre will perhaps regard this as an unacceptable compromise of artistic integrity. Those, on the other hand, who recognize the necessity of putting bread and butter on Creede’s communal table (sometimes not even the butter) make the best they know how of this kind of theatre from and acting and directing standpoint while taking comfort from the fact that several packed houses for a Neil Simon play will not only help insure the continued existence of the theatre but also help cover the partial loss of a not so packed house for a “Man for All Seasons” or a “Miracle Worker” both of which have been produced with surprising success by the Creede theatre.

The financial organization of the Creede theatre is of great interest to the business managers of other groups. The Jaycees nominally sponsor the group but all expenses are met directly from the box office receipts. The first two summers the theatre broke even but last summer it showed a four-thousand dollar profit which is quite unusual for a theatre in any circumstances. The actors are guaranteed a salary of ten dollars a week and at the end of the summer (after all expenses are paid) divide the profits among themselves–share and share alike. The actors and actresses live in the “Silver Palace” and share in all the cooking and housekeeping chores. There are no “stars” in the traditional sense in that every actor has a relatively equal number of large and small parts and every actor builds the scenery and works on costume, lighting, properties and sound effects on an equal basis. The pressures of living and working in such close quarters for three months are great, however, and at times tempers have come to the boiling point and even gone beyond. Yet, no disagreement has ever threatened the essential unity of the company or blighted the sense of purpose by which it is driven. The dream which inspired an exhausted cast to deliver a near perfect performance of “Mister Roberts” on that first night is still essential to the continued success of the Creede Theatre.

“Mister Roberts” was a brilliant success marred only by the live goat (which is called for in Act II) defecating all over the stage in the middle of performance. Needless to say, this unsolicited improvisation was thoroughly enjoyed by the Creede audience who called for an encore which was generously granted by this spirited if somewhat diuretic member of the the cast. “Operation Summer Theatre” opened four more shows (one a week) and ran them in repertory style. By the end of July there were five shows on five nights of the week. This kind of operation contains inherent difficulties: each night a set must be taken down and moved into storage and another put up in its place. It was not uncommon to see actors transporting scenery (the storeroom was across the street from the theatre) until one or two in the morning.

Certain changes and additions have been made since that first summer. The members of the company have changed so that only two of the original 1966 group have participated all three summers. The name has been changed from “Operation Summer Theatre” to “Creede Repertory Theatre.” It was agreed that “Operation” imputed to the organization an element of desperation that made it sound too much like what it actually was. In the summer of 1967 a children’s matinee was added on Wednesday and Sundays. The Theatre for Young People has brought in the repertoire “Tom Sawyer” and “Johnny Moonbeam” and introduced to the children of this small mining town the magic of the theatre. In addition to the plays of the first season the Creede Repertory Theatre has produced “Seven Year Itch,” “Arsenic and Old Lace,” “Bus Stop,” “You Can’t Take it With You,” “Miracle Worker,” “Out of the Frying Pan,” “Ten Little Indians,” “Green Grow the Lilacs,” “Barefoot in the Park,” and “Man for All Seasons.” Steve Grossman left the theatre after the second season to join the Peace Corps in Malaysia but the torch has passed to the younger talents who carry on the tradition. Next summer suggestions for shows have ranged from Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” or “Taming of the Shrew” to an evening of one acts featuring Albee and Pinter. Acceptance of theatre of that level of difficulty may seem “impossible” to some, but in its three year history the Creede organization has attempted to keep that word in quotation marks.

The future is unsure–Creede requires a high level of artistic discipline and personal sacrifice. The Creede actor gives over fifty performances in a summer season and often works a twenty four hour day. The average wage paid to the company members over the last three years works out to twelve cents an hour per capita. Whether the motivating spirit of the original dream can be preserved is a matter of uncertainty. Nevertheless, for three summers, defying every law of probability, the living theatre has come to Creede. –Joseph Roach